Productivity divergence:

- U.S. productivity growth has accelerated nicely, escaping from the subdued performance of the post-crisis era of just 0.5% to 1.0% growth per year, to a much improved – and more historically normal – 1.5% to 2.0% growth rate recently.

- Granted, this improvement still leaves it well shy of Alan Greenspan’s “productivity miracle” of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the IT revolution drove gains of 3% to 4% per year.

- Nevertheless, the doubling to tripling of the productivity growth rate is a welcome development. It has:

- increased the financial standard of living of Americans

- taken pressure off hiring (at least in terms of what is needed to sustain a decent rate of GDP growth)

- increased the odds that the business cycle can continue to chug along for longer before it overheats

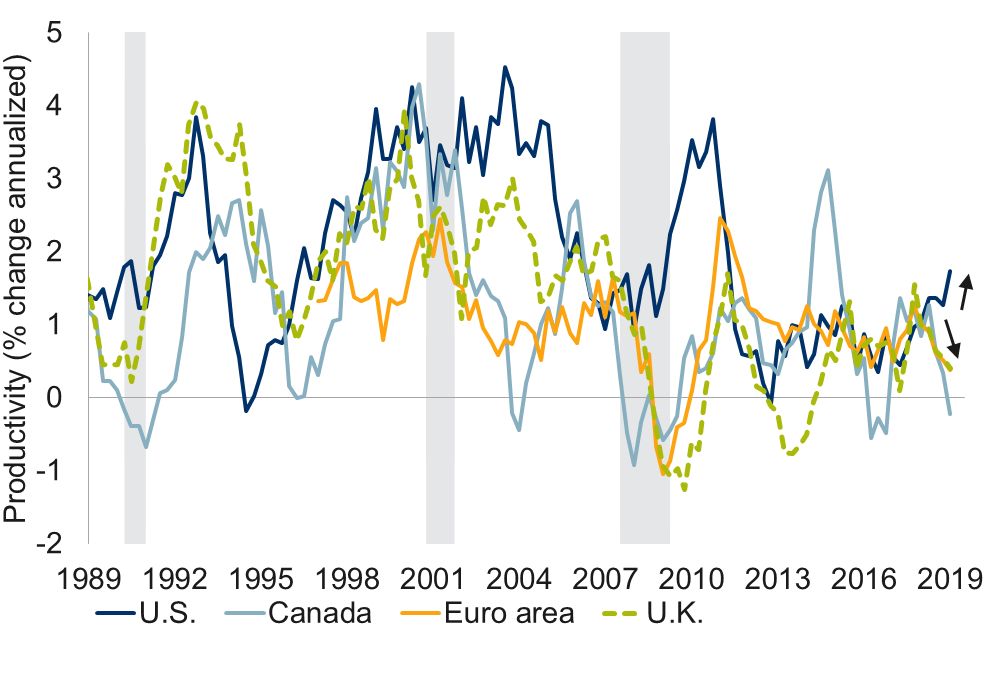

- A surprising development is that other developed countries have not shared in the recent U.S. success (see chart).

-

Productivity divergence: U.S. vs. other developed countries

Note: As of Q1 2019. Productivity measured as rolling 8-quarter annualized % change of the business sector/total economy real output per hour of all persons. Shaded area represents U.S. recession. Source: NBER, Haver Analytics, RBC GAM

- There are several theories that could explain this productivity divergence:

- The divergence could simply be random noise. Productivity is a particularly jittery series, prone to accelerating and braking for no apparent reason from one quarter to the next. However, we reject this notion: when we smooth the series via an eight quarter rolling window, the divergence is still stark.

- The U.S. delivered aggressive tax cuts, potentially providing businesses with the funds necessary to enhance their productivity. While a superficial glance at the data supports this theory – U.S. business investment growth has been fairly good over the past few years – a deeper looks contradicts it. Measured precisely, the U.S. capital intensity – the capital stock as a ratio to GDP – has actually been declining slightly as capital investment after depreciation failed to fully keep pace with the rate of economic growth. Supporting this, measures that disaggregate U.S. productivity growth into its base components find that capital investment has contributed little to recent productivity growth, with most of the pop instead coming from the more amorphous multi-factor productivity input.

- Retreating from the tax cut theory without quite abandoning it altogether, it strikes us that recent U.S. fiscal policies – a mix of tax cuts and deregulation – may have created an “open for business” environment in the U.S. that has emboldened innovation and encouraged more entrepreneurship. These two things can theoretically help productivity via channels other than cap ex, and could in principle show up via the very multi-factor productivity channel that has perked up over the past several years. This is a viable explanation.

- Many of the world’s corporate tech champions and a large fraction of the world’s technology start-ups are domiciled in the U.S. These companies:

- enjoy gigantic cash hordes

- sport gargantuan cap ex budgets

- attract many of the world’s smartest technology workers

- engage in a great deal of research and innovation

- Finally, it has historically taken up to a decade for economies to fully recover from a financial crisis. It is thus tempting to argue that the recent U.S. productivity acceleration represents the country finally escaping from the gravitational pull of the 2008—2009 financial crisis. Moreover, because the U.S. exited the global recession first/most vigorously and then gobbled through its economic slack first, it may simply be a year or two ahead of everyone else. Optimistically, this suggests that other countries could start to enjoy a productivity acceleration over the next few years.

However, there is a hole in this theory. The argument that it takes a decade to recover from a crisis is frequently misinterpreted. The proper interpretation is that all evidence of a crisis is usually gone after a decade, meaning that the level of GDP per capita has risen to where it would have been had the recession and subsequent period of sluggish growth never happened. Thus, it isn’t enough simply to return to a more normal growth rate – there should also be an unusually rapid catch-up period afterward. That hasn’t happened this time. To the contrary, the productivity pickup was arguably long overdue and still a bit underwhelming rather than being right on time and on scale. Thus, the post-crisis pattern isn’t especially clean.

Still, let us not completely abandon the idea that the U.S. could simply be leading other countries in a productivity revival. Even if the time period doesn’t fit particularly crisply with historical crises, the fact remains that the U.S. escaped from the financial crisis with the greatest vigour and ate through its economic slack before most other countries. It could still be the case that other countries will also enjoy a productivity pickup after they have whittled away the last vestiges of their own economic slack in the coming years.

Providing some theoretical support to the notion of a late-cycle productivity acceleration, there has long been the idea that productivity growth should naturally improve when workers are in short supply as companies must find other ways to grow their profits. Indeed, a simple correlation of U.S. productivity growth and the output gap over the past 70 years reveals a positive correlation between the two. - There are several useful takeaways from this analysis.

- As discussed earlier, the fact that U.S. productivity growth has accelerated highlights the rising financial well-being of Americans, reduces the U.S. economy’s vulnerability to a slowing job market, and raises the possibility that the business cycle could extend for longer without overheating.

- Among the reasons why U.S. productivity growth has picked up while others have not, the most plausible explanations involve:

- growth-positive business policies

- the massive U.S. tech sector

- U.S. economic leadership

- Of these productivity drivers, the first could be replicated by other countries if they desired. The second element is likely beyond their realistic grasp. The third argues that some amount of productivity pickup should arrive on their shores regardless of their public policies.

U.K. prime minister:

- On Tuesday July 23, the U.K. will anoint its next Prime Minister from the ranks of the Conservative Party. Boris Johnson is almost certainly the victor. The former mayor of London is also an ex-cabinet minister. Stylistically, he is oft criticized as lacking gravitas and is considered ideologically flexible (for better or worse).

- For this last reason, it is unusually hard to project public policy initiatives as a result of his ascension.

- Of course, there is only one policy issue of any great relevance in the U.K. at present: the prospects for Brexit.

- Johnson’s rise to prime minister has been anticipated since the beginning of June when Theresa May tendered her resignation, and his stance on Brexit has been consistent over that period: he wants a deal with the EU, but dislike’s May’s proposed interim deal that included a guarantee of no hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Furthermore, he refuses to extend negotiations beyond the existing October 31 deadline.

- As such, without a deal and with just three months to go, there is the very real risk of the U.K. crashing out of the EU in the harshest Brexit possible.

- His strategy, then, is very clearly to pressure the EU into offering a better deal to the U.K., ideally permitting the unencumbered exchange of goods, services and financial flows, without allowing the free flow of people.

- It is far from clear to us that the EU will be willing or able to make substantial concessions, nor that there is enough time left to pen a new deal:

- U.K. parliament will soon be in recess through early September, while the newly elected European Commission members will not take office until the day after the deadline (November 1).

- All 28 EU members possess a veto, meaning just one objection is enough to kill a deal.

- The EU has already made clear that it is not willing to create an à la carte menu for the U.K. that would slice and dice the “four freedoms.”

- From a game theory perspective, the EU enjoys the negotiating advantage by virtue of its considerably larger size, as the EU would be hurt much less by a hard U.K. exit than would the U.K. itself.

- The EU must ensure it doesn’t give the U.K. a sweetheart deal as might tempt other countries to seek superior arrangements outside of the confines of the EU. This is a particularly serious risk at a time of swelling populism.

- The question thus becomes if Boris Johnson is bluffing and will ultimately back down. This isn’t clear. He has indicated he thinks it is extremely unlikely that the U.K. will fall out of the EU without a deal. But it is unclear whether this is a tacit acknowledgment of his own unstated backup plan to a) accept Theresa May’s deal or b) request another extension; or instead the unrealistic expectation that the EU will bend.

- While the risk of a hard Brexit has clearly gone up and we currently peg this at a substantial 20%, this also implies that other outcomes are even more likely. We do not rule out a soft Brexit involving minor tweaks to the Theresa May proposal. Similarly there are a variety of routes to the cancellation of Brexit altogether.

- Already, several cabinet ministers – Philip Hammond, Alan Duncan and David Gauke, among them – have resigned or will shortly resign in protest of the Johnson plan for Brexit. Combined with significant opposition to the plan across the broader parliament and some sympathy from the Speaker of the House of Commons, it is quite easy to envision a vote of no confidence triggering another election.

- Given the fracturing of public support over the past three months, the outcome of a theoretical election is hard to read. Whereas the Conservatives and Labour had roughly 40% and 37% support respectively just a few months ago, these now sit at just 22% and 23%. Meanwhile, the Brexit Party has exploded from just 3% support to 22% today. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be staging a recovery, up from roughly 8% to 19% support. Thus, there are now four parties all with between 19% and 23% support, pointing to an almost assuredly hung parliament and a mad scramble to form coalitions or at least alliances.

- To the extent the Liberal Democrats play kingmaker, they would almost certainly insist on “No Brexit” or least a second referendum as a condition. On the other hand, if it is the Brexit Party playing kingmaker, they would presumably demand a fairly immediate and hard form of Brexit.

- The bottom line is that more than three years after the initial referendum and with a third prime minister set to govern during this period, no one is truly any closer to understanding how Brexit will conclude. Virtually all options are still on the table.

- Perhaps it can be said that the most extreme outcomes are rising in probability – a hard Brexit or no Brexit – whereas the more middling options have shrunk somewhat. But all are still very much in play.

U.S. 2020 election:

- We make a habit of regularly reviewing the outlook for the potentially pivotal 2020 U.S. election.

- President Trump looks increasingly likely to carry the Republican mantle into battle given the apparent reluctance of Democrats to initiate impeachment efforts and the fact that an elected president has only failed to capture their party’s nomination once – Franklin Pierce in 1852. For their part, betting markets assign an 89% chance that Trump will be on the ballot for the Republicans.

- The Democrat side requires additional analysis, as the journey begins with more than 20 candidates. This is an unusually large field, and it happens to be an unusually left-leaning group as well.

- Indeed, the market’s primary anxiety about the election is that voters could be forced to choose between a populist Republican and a far-left Democrat. Neither would come close to the centre/centre-right stance best preferred by corporations and financial markets.

- There are four leading Democrats:

- Former vice-president Joe Biden is a middle-of-the-road Democrat and polls best, with around 27% support. However, his support is currently on the downswing.

- Senator Elizabeth Warren is a left-wing Democrat with around 17% support and rising. Her rise has been by far the steadiest of the bunch, suggesting a degree of positive momentum to come.

- Senator Bernie Sanders is a far-left Democrat who also enjoys around 17% poll support, but is actively slipping.

- Senator Kamala Harris is a left-wing Democrat with around 13% support who enjoyed a recent sharp surge in support, though has suffered a notable subsequent decline.

- No other candidate has reliably more than half of Harris’ support, though there are still six months until the first state primary in Iowa, so any of a number of other candidates could yet surge to prominence.

- Interestingly, betting markets have the odds of victory slightly different than the polls:

- Joe Biden and Elizabeth Warren converge to a 23% dead heat, Kamala Harris rises to 21%, Bernie Sanders falls to 14%, and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg rises to 11%.

- One has to imagine that a substantial consideration for markets is the extent to which many of the left-wing candidates cannibalize one another, allowing for a more middle-of-the-road Democrat like Joe Biden to waltz away with the nomination despite his baggage.

- Similarly, the Democrat Party itself will need to make a tough judgement between candidates who promise the moon and align perfectly with the Democrat party base – increasing turnout – versus those who may align less perfectly with Democrat policy ideals but have a better chance of picking up independent and cross-party voters.

- In polls that pit particular Democrat candidates against President Trump in a head-to-head matchup, Joe Biden fares the best with a theoretical 9 percentage point lead. This is presumably because of his potential ability to capture independents. Bernie Sanders fares next best, winning against Trump by 7 points, arguably with the opposite strategy of a highly motivated but concentrated base. Elizabeth Warren has a theoretical 5 point lead over Trump, while Kamala Harris squeaks out a 1 point lead.

- An interesting conclusion, then, is that the Democrats appear set to win almost regardless of who they put up against Trump.

- More generic polls confirm this, giving the Democrat nominee a 53.5% chance of beating the Republican nominee for the presidency in 2020.

- But it is dangerous to view this as a pre-ordained conclusion or to cease caring about which Democrat candidate is chosen:

- A 53.5% chance is barely different than a coin toss.

- The margin for error is radically different depending on the candidate.

- Much could yet change between now and the election.

- The dirty laundry of many candidates has not yet been aired.

- Trump had merely a 30% to 40% chance of victory on election night in 2016 and managed to claim the win.

- It is a rare occurrence for an incumbent President to lose given the prestige of their office, their name recognition and the presidency’s great privileges. A war – whether military or trade – could yet rally further support for Trump.

- To some extent, the political polarization of the last few decades makes it hardly surprising that we now operate in a world in which the two presidential candidates are likely to possess radically different views of the world and policy prescriptions. There are no Bill Clinton-esque centrists in the race this cycle. That makes the election especially pivotal, as policies could swing sharply in one direction or the other.

- Markets should take some heart from the fact that:

- The most moderate presidential candidate will probably have the best chance of winning.

- Politicians usually tack somewhat toward the centre after election (though Trump is an exception).

- Very little legislation is likely to be passed even if a far-from-centre candidate is elected given that Congress will probably remain divided after the election (72% chance the Senate remains Republican; 67% chance the House remains Democrat).

- Of course, Presidents do get to administer tariffs, implement foreign policy, issue executive orders, nominate Federal Reserve Governors and appoint Supreme Court judges. It is still very much a race worth watching.

Debt ceiling:

- The U.S. debt ceiling rises to prominence when the country’s chronic budget deficit threatens to increase the public debt load beyond a government-determined limit.

- It goes without saying that the debt ceiling is a redundant lever to the extent that politicians already set the national budget, from whence deficits and surpluses (and thus a rising or falling public debt) arise.

- Nevertheless, the debt ceiling is a reality, and has been raised without (too much) incident on 74 occasions since 1962.

- U.S. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin has indicated that the debt ceiling limit will be struck in early September, creating a sense of urgency for a deal between Democrats and Republicans.

- The risk of default is itself fairly low, and the risk of a market panic is extremely low:

- There are a variety of practical and not-so-practical ways that the Treasury can forestall a default. These range from prioritizing debt-servicing payments over other government obligations (such as by deferring salaries or pensions, either of which would get voters screaming and bring politicians back to the table very quickly), to the notion of issuing a “trillion dollar coin” that would offer something of a funding loophole, to a closer inspection of the Constitution’s 14th amendment that promises to “protect the full faith and credit of the United States.”

- Moreover, even if the U.S. did somehow default on its debt, the market would immediately recognize that it was a temporary political matter, and that the U.S. economy and government are entirely capable of servicing their debts.

- That said, debt ceiling battles can be a distraction. At an extreme there can be some minor market consequences such as the episode in 2011 that ultimately prompted S&P to downgrade the U.S. sovereign debt rating from the pinnacle of AAA to AA+.

- The debt ceiling decision is just one part of what could prove a busy autumn, with the usual September 30th fiscal year-end that will require a new budget for the subsequent year, and the possibility that a mishandling of that budget could induce a year-end fiscal cliff wherein temporary (but normally renewed) spending measures fail to be extended. This happened in an extreme fashion in January 2013, doing non-trivial economic damage.

- The good news is that the prospect of a debt ceiling deal seems fairly close at hand. The media is reporting that a deal is “near final” as of July 22, and Democrat House Leader Nancy Pelosi is keen to strike a deal before the House goes on its summer break on Friday July 26. The remaining differences apparently relate to “technical language issues”, which frankly could mean almost anything, but give the impression of being fairly narrow.

- If successfully approved, the debt ceiling would likely be extended for two years, through July 31, 2021. Attached to this extension is supposed to be a commitment to cut certain forms of government spending by something like $80 billion, though the figure $150 billion has also been bandied about.

- At present, we are optimistic a deal will be struck. However, given the government shutdown in December 2018, it is far from assured that normal protocol will be followed this time. If a deal is not struck this week, prepare for messiness and the possibility of hair-raising moments in September. Ultimately, though, we believe the worst-case scenario is extremely unlikely.

Data run:

- A quick word on the U.S. GDP report coming out later this week. The consensus looks for just a 1.8% annualized increase in Q2 2019, with the arguably superior Atlanta Fed GDPNow index pointing to an even lower 1.6% print. There is nothing disastrous in either of these outcomes, though they would represent the feeblest quarterly growth rate in over three years.

- While it is undeniable that various metrics point to slowing global and U.S. growth, and that this release will be used as a further excuse for a precautionary Fed rate cut, any acute concern is overblown.

- The composition of the report is likely to reveal strong consumer spending growth, with most of the weakness confined to external or artificial categories. Net exports are set to subtract 0.5 percentage points from growth. This is undeniably a reflection of protectionism, but it simultaneously means that U.S. domestic demand is likely better than the GDP number will suggest.

- The same goes for inventories, which are expected to subtract a big 1.0 percentage point from the growth figure. This inventory drawdown means that producers did temporarily expand their output by less than normal, but that demand growth was notably better than the GDP number itself.