For many, Black Friday sounds the unofficial starting gun for the holiday season. For me, however, it already rang out late last week when a motley band of Scouts, leaders and parents gathered in the dark on a rain-soaked hill to heave several hundred Christmas trees from the back of a truck into waiting pens. This was the seventh consecutive year that I’ve participated in the ritual.

As fundraising efforts go, our group has always figured that working a few shifts selling trees is surely preferable to pressuring colleagues and friends into buying thousands of dollars of apples or popcorn.

But afterwards, as I was trudging home through the driving rain, I got to wondering just how true that assumption is. What goes uncounted are the sap-stained coats, the tweaked lower backs, the hours spent setting up and tearing down, the considerable peril of operating a chainsaw (ok, more of a turkey carver), the anxiety of affixing a scratchy tree to the roof of someone’s brand-new car, and the slick salesmanship needed to sell those final few “Charlie Brown” trees to skeptical customers.

But for all of my Scrooge-like griping, I must confess that I never feel a stronger sense of community than I do when setting up those trees and working those shifts. Not everything can be tallied up in dollars and cents, it seems. Anybody need a tree?

Growth bottoming out?

- One encounters mounting claims that economic growth is finally bottoming out after two years of deceleration.

- Just how true is this assertion? We find there is some tentative evidence in its favor, but that conclusive proof does not yet exist.

- We begin in the U.S., where there are indeed several examples of improving economic indicators:

- Prominently, the ISM (Institute for Supply Management) Manufacturing Index and the ISM Non-Manufacturing Index both managed to rise with their latest readings, reversing what had been an uninterrupted string of six consecutive monthly declines for the former. To be sure, the level is still quite low.

- Meanwhile, the less publicized Markit Manufacturing Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) for the U.S. rose from 51.3 to 52.2 in November – its third consecutive monthly gain off of an August low. The Markit Services PMI also rose.

- The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) shows a slight rebound in hiring and capital expenditure intentions among small American businesses.

- There is also a smattering of improvement internationally:

- Germany’s critical IFO (Information und Forschung – Institute for Economic Research) index is also on the rise, having bottomed in August as well.

- More broadly, the Eurozone manufacturing and services PMIs have also risen in their latest readings.

- However, the trend is far from universal:

- There are also various points of weakness in the U.S., including:

- a data change index that remains negative (though less so)

- a surprise index that is slightly negative, and

- Q4 GDP that is tracking a paltry +0.4% annualized, what would be the weakest quarter in four years.

- Internationally, while certain aspects of the U.S., Germany and Eurozone look improved, other areas do not.

- Japan’s closely-watched Tankan survey continues to decline

- the U.K.’s two key PMIs have both fallen again

- three of China’s four PMIs are down, and

- the global data change index remains negative (though decreasingly so).

- There are also various points of weakness in the U.S., including:

- The bottom line is that economic data was universally grim a few months ago, whereas now there is a mix of good and bad. It is probably premature to claim that growth is actively rebounding, but it might just be flattening out. The evidence is strongest in the U.S., and it is perhaps promising that PMIs – which include forward-looking components – have improved first, as that may plausibly lead to better GDP and activity data later.

- Theoretically, a bottoming in growth this fall and into early 2020 would make sense due to the substantial improvement in financial conditions so far in 2019. But there are many other variables at play, including:

- the ongoing friction of tariffs

- a fiscal drag (though this is shrinking as government’s pivot toward stimulus), and

- the residual headwind of policy uncertainty.

U.S. consumers:

- Much as all roads lead to Rome, all economic analysis eventually comes down to the consumer.

- In the developed world, consumer spending constitutes the great bulk of economic activity. In the case of the U.S. it represents nearly 70% of GDP.

- The sector is often the last line of defense against recession given its relatively stable trajectory when compared to other GDP components such as business investment, trade and inventories. Indeed, U.S. real GDP ex-consumption has declined in each of the last two quarters, meaning that the U.S. economy would have met the quick-and-dirty definition of a recession were it not for rising consumer spending.

- Fortunately, U.S. consumers are in decent shape. Job growth remains more than sufficient to absorb new entrants to the labour force, wage growth is the best it has been this cycle, household leverage has been reduced, borrowing costs are ultra-low, the household savings rate is unusually high and consumer confidence remains fairly good.

- Reflecting this, retail sales growth remains solid, if down slightly from its earlier rate of expansion. And consumer spending on durable goods continues to rise – a positive signal as this tends to lead broader consumer activity.

- Why then, are we at least a little anxious about consumer spending? There are several reasons.

- The margin for error is unusually slim given that other sectors have not been contributing reliably to economic growth.

- There is some tentative evidence that the labour market – the main driver of consumer spending – is peaking:

- All three measures of U.S. business hiring intentions that we track have weakened when compared to the prior few years (though the latest month has brought a small rebound across the board).

- Measures of hiring, hours and compensation growth have slowed. Simple job growth has ebbed from +1.8% year over year (YoY) a year ago to +1.4% YoY today. Aggregate private-sector hours worked has declined from +2.0% YoY to +1.1% YoY. Total private-sector compensation has slipped from +5.3% YoY to +4.6% YoY. None of these are bad, but each is trending in the wrong direction.

- Secondary labour force metrics such as job openings have begun to slip after a decade of nearly uninterrupted improvement. On a similar note, jobless claims have seemingly stopped falling, and may even be starting to edge higher.

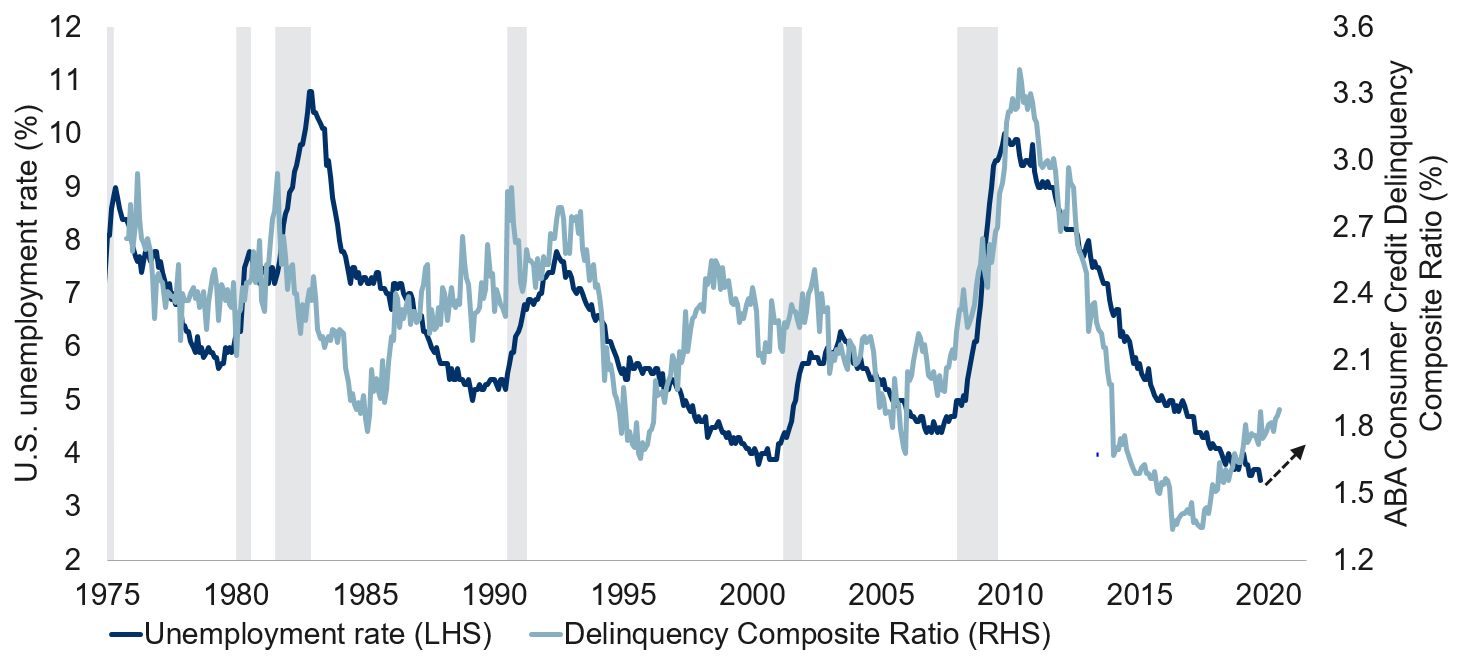

- Finally, consumer loan delinquencies have begun turning higher. Historically, this has presaged an increase in the unemployment rate (see chart). In turn, any significant increase in unemployment usually snowballs into recession. Granted, the connection is imprecise between each of these variables.

-

U.S. unemployment rate to rise

Note: Unemployment rate as of Sep 2019, Delinquency Composite Ratio in 12-month lead as of Jun 2019. Source: ABA Consumer Credit Delinquency Bulletin, Macrobond, RBC GAM

- Our best guess remains that consumers have sufficient gumption to keep the U.S. economy on track. After all, hiring is good, wage growth is strong and debt levels are low. But a few cracks are showing, and any broadening of those cracks might reveal a path toward recession.

Tech change and job loss:

- Technological progress provides a myriad of benefits to society, ranging from greater wealth to additional leisure to cheaper products.

- But all of this good is offset by rising concern that the rapid rate of technological progress may permanently displace workers to the point of creating a structural underclass of unemployed people.

- Fortunately, that has not been the experience so far, at least at the aggregate level. While automation, computers and robots have indeed displaced significant numbers of workers in some sectors, other sectors have always managed to pick up the slack, resulting in the lowest economy-wide unemployment rate in half a century.

- More often than not, the creative destruction induced by technological change replaces old companies and jobs with even better ones.

- History provides many examples of major employment shifts without a permanent underclass of unemployed forming:

- The most striking example is the rapid contraction in agricultural employment. At the turn of the 20th century, roughly 40% of Americans lived on a farm. Today, that figure is in the realm of 1%. The unemployment rate did not spike by 39 percentage points – instead, those people were absorbed into other sectors of the economy because they possessed some amount of general human capital and so had the ability to contribute in some other fashion.

- Other smaller examples of technological disruptions include the decline in the ranks of secretaries (and human computers, for that matter) with the advent of the personal computer, the decline of telephone operators, bank tellers, milkmen, elevator operators, and so on.

- A widely cited study from Oxford University was purported to have claimed that 47% of jobs could be automated over the next decade or two. However, a closer reading reveals that 47% of jobs are simply described as being at a high risk of replacement relative to other forms of employment. No claim is made as to the fraction of such jobs that might disappear.

- Frequently, computers end up complementing the work that a human does, rather than replacing it. The quality of the output goes up rather than the amount of workers going down, be it pattern recognition software helping a radiologist identify a mass or a portfolio manager selecting a security to invest in.

- It is also important not to underestimate the complexity of many jobs – the remarkably diverse array of talents and skills that a robot would have to possess to fully supplant a human worker. A school janitor, for instance, must be capable of taking direction from the principal, cleaning a toilet, washing the floor, replacing a light bulb, fixing a chair, and even making a judgement as to when artwork on the wall can be thrown out. General purpose robots that can do all of these things are likely many years away, let alone at a cost below that of a human janitor.

- It isn’t even clear that the rate of technological advancement is especially fast right now. Official measures of productivity growth (flawed though they may be) argue that productivity growth is actually running more slowly than normal right now.

- Thus, for these many reasons, a high level of technology-induced unemployment seems unlikely in the near or medium term.

- But it is not an impossibility over the long run. There are several arguments as to how this time could indeed differ from the more benign technological advances of the past:

- The cost of some trainable industrial robots now amortize to no more than a few dollars an hour – below the minimum wage and thus cheaper than any developed-world human. In theory, these devices can be deployed for many types of repetitive manual labour. That said, this is not so radical a development as it first seems – many things can be done more cheaply by machines. This is why society has had machines of various forms for thousands of years. Each is technically eliminating a job that a human could do, but where would we be if books were copied by hand and wheat was torn from the ground rather than cut by a blade?

- Whereas agricultural productivity increased steadily over the span of decades, allowing time for farmworkers to gradually find alternative employment, it is fair to concede that the changes occurring today could be more abrupt. The combination of computers and the internet is resulting in a previously impossible scalability that allows one person to service a million clients nearly as easily as servicing a hundred. Much of the brick-and-mortar retail sector is being displaced in one fell swoop by online stores. Trucking and taxi employment may be eliminated by self-driving vehicles.

- Computers have been better at doing calculations and remembering things than humans for many decades. They are now gaining new abilities which may unleash a further wave of disruption. New capabilities include the ability to learn dynamically via machine learning and significant advances in sensing that open the door to jobs that require interaction with the world in a physical way. Should sensing abilities continue to advance, a general purpose robot could well replace many manual jobs in one fell swoop.

- It is perhaps relevant that whereas humans have never been permanently displaced from the labour market before, other beings have been. In the late 19th century, there was roughly one horse for every three Americans, and nearly all were integral to the functioning of the economy. Today, there are far fewer horses due to the spread of motor vehicles, and those that remain play almost no role in the economy. It is not impossible that humans could also lose their role in the economy should sufficiently advanced technologies come along.

- To reiterate, we acknowledge a higher than normal risk that unemployment rises structurally, but it is not a certain outcome.

- Nevertheless, what might policymakers do in a scenario involving large numbers of structurally unemployed?

- A basic income or more generous welfare benefits would become a political necessity to the extent that a significant fraction of the population (and voter base) was unemployed.

- To the extent that the owners of labour-replacing robots would presumably be benefiting from the replacement of humans with robots, it is likely that policymakers would seek greater tax revenue from this group via higher corporate income tax rates, and would ensure that technology firms were not engaging in geographic arbitrage of their tax rates.

- To the extent that the most skilled workers would still likely be required to program and operate a world run by automation and robots, top personal income tax rates would likely rise.

- It is notable that many of these ideas have figured prominently in the early stages of the 2020 U.S. election campaign.

- Should the structurally unemployed be provided with a sufficient living wage by the state, an optimist would expect society to be filled with contented people pursuing creative endeavours and personal passions. A pessimist would expect a breakdown in society, not only given the gaping divide between workers and the jobless, but because many people derive a sense of meaning from their employment and might otherwise feel adrift.