I recently had the opportunity to hold in my hands a gold bar worth several hundred thousand dollars. It was surprisingly small given its value, yet unexpectedly heavy for its size. I was sorely tempted to swap the gold for a similarly-shaped stick of butter that I always keep in my desk should just such an opportunity arise. But it was lucky that I resisted that instinct as the next person insisted on taking a selfie while biting the gold. Though gold is famous for its malleability, it is not known for melting in your mouth.

Possibly as penitence for my avarice, I then spent Saturday night with our local Scouts troop, sleeping in the bowels of a World War II-era cruiser. If the quadruple bunk beds and 30 people to a room weren’t enough, night-watch duty surely absolved me of my sins.

Canadian election:

- This #MacroMemo was written before the Canadian election results were announced. We’ve since posted a post-election commentary from RBC Global Asset Management on our website.

Worse data versus smaller risks:

- There is good news and bad news regarding the economic environment.

- The bad news is that the global growth trend is still mostly weakening.

- The good news is that some of the biggest downside risks have shrunk somewhat.

- Overall, we feel a little better about the macro situation, though the declining growth trend is not trivial.

- Weakening economic indicators:

- A host of purchasing manager indices continue to weaken, headlined by the ISM (Institute for Supply Management) Manufacturing Index that now sits at a subterranean 47.8.

- Briefly, U.S. and Chinese economic surprises had flipped into nicely positive territory. However, Chinese surprises are now firmly negative and descending. U.S. surprises are still slightly positive, but also in clear retreat.

- Economic data-change indices remain steadily negative.

- Diminishing downside risks:

- The worst downside risk for Brexit – a no-deal exit – has shrunk, though not vanished (see next section).

- S.-China trade talks achieved at least a superficial détente (see later section).

- There is some evidence of Chinese stimulus beginning to trickle forth. This is not so much visible in the likes of GDP or retail sales as in precursors such as the Chinese money supply growth and credit growth. The default assumption should probably remain that Chinese growth will continue to slow, but the upside risk of stabilization is mounting, particularly given the nimbleness of Chinese policymakers.

- The U.S. yield curve has recently un-inverted. Not only is the 2yr-10yr spread now positive again, but even the 3m-10yr spread has now reverted to a positive slope. An inverted yield curve is a classic recession indicator. Be warned, however, that the yield curve is still preternaturally flat. The NY Fed’s recession risk model indicates a 1-year ahead recession risk of 28% – down from a peak of 43%.

- We pay slightly more heed to the shrinking risks rather than slowing growth because the former will be key determinants of the latter over the coming year.

Brexit update:

- The Brexit situation remains highly fluid.

- A week ago, British Prime Minister Johnson struck a tentative transition deal with the EU, allowing for a reduced Irish-to-Northern Irish border in exchange for an increased Northern Irish-to-the rest of the U.K. border.

- However, this deal required U.K. parliament’s approval. A special sitting of parliament on Saturday October 19 (the first such Saturday meeting since the Falklands War) failed to achieve the necessary support. Instead, parliament passed a measure that requires all necessary supporting legislation for Brexit to first be prepared and scrutinized before allowing for a vote on Brexit itself. This may take days or even months.

- The failure triggered a piece of legislation that had been implemented in September to automatically request a 3-month Brexit extension if no deal had been secured in the days leading up to the October 31 deadline.

- Although Johnson is opposed to an extension, his government nevertheless made the request as required by law. The absence of his signature from the relevant document is not viewed as problematic by the EU.

- Germany had indicated that an extension should be forthcoming, though formal approval requires unanimous support by all 27 EU nations. This leaves at least the small risk of a No Deal.

- An effort by Johnson to force a second vote on his exit terms, on October 21, was blocked by the Speaker of the House of Commons on the basis that it was too similar to the question already put to parliament on October 19.

- There is a decent chance of Johnson’s proposal ultimately being approved as it:

- already enjoys the support of nearly half of parliamentarians

- proposes a fairly middle-of-the-road Brexit transition

- bears a considerable resemblance to former Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposal which only barely failed to be approved earlier in 2019.

- Whether that approval might come in the next few days or instead over the next several months is not yet clear.

- Given that an extension has now been requested and a viable transition deal is again on the table, the odds of a No Deal Brexit continue to shrink. This is good.

- However, considerable uncertainties remain. Not only is the extent of any extension uncertain – the EU does not have to abide by the British request for three months, for instance – but further tweaks to the transition deal may yet be necessary:

- Politicians could opt to put any proposed deal to a referendum.

- Parliamentary stability is low, with the implication that a snap election is a constant possibility.

- Arguably above all else, the great bulk of negotiations between the two parties have so far merely concerned the temporary transition arrangement between the U.K. and the EU as opposed to the final relationship. That last item will be a subject for negotiations once the transition is underway.

U.S.-China negotiations:

- It has now been 10 days since the U.S. and China reached a tentative, superficial trade agreement.

- It is certainly good news when compared to the counterfactual scenario of a doubling-down on tariffs as played out in the middle of 2019. However, there is little that is firm in the agreement.

- Terms like “in principle” and “Phase 1 deal” don’t lend much strength to the solidity or finality of the agreement. In fact, much of the agreement is not yet written down, has not been signed, and the Chinese negotiators are thought to need to “sell it” to Chinese policymakers before anything can be finalized. The November APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) meeting in Chile is viewed as an opportunity to truly finalize the deal.

- Recall that negotiations were proceeding swimmingly between the U.S. and China last spring – with talk of imminent finalization – when the entire agreement unraveled and tariffs unexpectedly leaped higher.

- China promises to buy more U.S. agricultural goods, adjust its intellectual property (IP) laws, and reduce its intervention in the currency market. However, this may be thinner gruel than first appears as China has repeatedly made the same promise to buy more agricultural products and China has been actively seeking to defend rather than to depreciate its currency for some time. The intellectual property news could be substantial given its centrality to U.S. complaints, but much depends on what exactly China delivers.

- Both parties made progress toward some sort of dispute-resolution mechanism, though it doesn’t appear to be complete and both countries are famous for balking at international oversight.

- For its part, the U.S. delayed a tariff increase that had been scheduled for October 15, and should a deal actually be struck it would be logical if the U.S. also delayed/cancelled the planned December 15 tariff increase.

- While these developments are tentatively positive, they probably do not represent a comprehensive or enduring solution to the U.S.-China relationship. Furthermore, the U.S.-Europe trade disagreement is heating up and auto tariffs may re-emerge as a threat in mid-November.

- We hold open the possibility that economic weakness eventually convinces the White House to back off of tariffs as the 2020 elections near. But China’s asymmetric advantages remain a very real concern for the U.S. and as such are unlikely to be completely papered over.

The Fed’s new quantitative easing:

- After the U.S. repo market blew wider last month, the U.S. Federal Reserve indicated that it would find a way to improve the functioning of the market.

- While part of the repo market’s problems were the result of idiosyncratic stressors including a large Treasury bill auction and the quarterly deadline for corporate income tax payments, U.S. banks have also indicated that some was the result of banks feeling compelled to keep extremely large reserves of liquid assets in light of the onerous bank regulations that have come about over the past decade.

- To address at least part of the problem, the Fed has now begun purchasing a substantial US$60 billion of Treasury bills each month, for a minimum period of seven months. This will both hold down money market rates and increase the supply of excess reserves to banks.

- The Fed insists that these actions should not be viewed as “quantitative easing” in that the purchases are occurring at the extreme short end of the curve rather than out the curve and because the purpose is not to inflame risk appetite.

- While we agree that the basic purpose is not to boost economic growth, the action nevertheless fits our own definition of quantitative easing: the use of newly printed money to permanently acquire debt securities. As a result, the monetary base has increased and a downward pressure has been applied to bond yields.

- The fact that the downward pressure is occurring primarily at the short end rather than the long end of the curve as in prior rounds of quantitative easing is relevant but not a deal-breaker: after all, the Fed conducts most of its monetary policy at the short end of the curve and this still constitutes stimulus.

- The size of the operations is not trivial: a minimum of 7 months of US$60 billion in monthly purchases constitutes no less than US$420 billion. This will take the Fed’s balance sheet close to its all-time peak, essentially unwinding the prior quantitative tightening effort.

- Does the Fed’s new action presage the re-introduction of traditional large-scale quantitative easing? Not necessarily, though the fact that the Fed is again cutting its policy rate and dabbling in bond-buying suggests that it would not be a great leap.

A primer on low and negative rates:

- The world is presently operating in an environment of incredibly low interest rates:

- As much as US$17 trillion of global debt has traded at a negative interest rate (see first chart).

-

Share of bonds with negative yields surged

Note: As of 10/18/2019. Percentage of bonds in Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index trading at negative yields. Source: Bloomberg, RBC GAM

- Eurozone and Japanese policy rates are now themselves negative. This means that negative yields aren’t just a distortion of the market but something that is sanctioned by the highest authorities.

- Perhaps most astonishing of all, Greece just managed to issue its first negative-yield bond despite suffering through a massive debt crisis just a few years ago.

- The story isn’t over yet: over the past year, central banks have been more inclined to reduce rates than to hike them, and the European Central Bank (and, debatably, the Fed) have returned to outright bond-buying.

- Why are interest rates so low?

- Slow real growth tends to map onto low real interest rates because bond yields act as the hurdle over which investment decisions must clear, and the prospective rate of return in a slow-growth environment is low.

- Low and relatively stable inflation tends to depress the inflation-expectations component of nominal bond yields. Given an aging population alongside globalization and automation, inflation is unusually restrained.

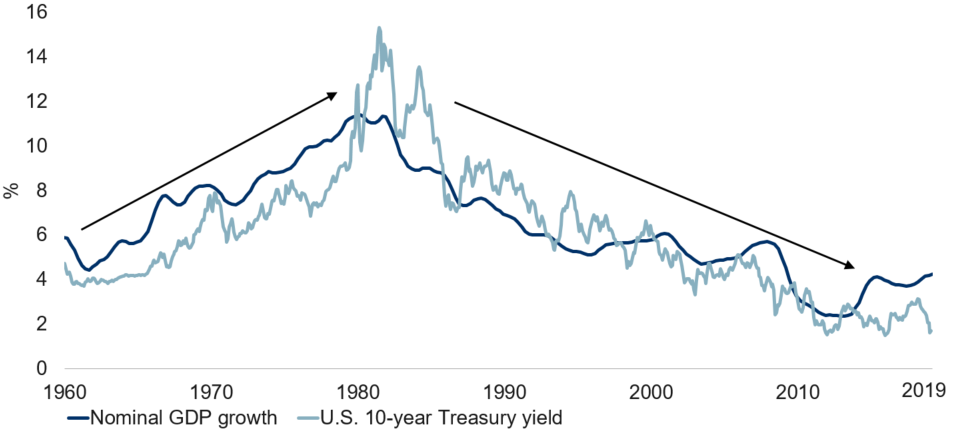

- Combined, nominal interest rates have tracked nominal economic growth lower over the past several decades (see next chart).

-

U.S. nominal GDP and 10-year yield in tandem

Note: U.S. Treasury yield as of Sep 2019. 5-year moving average of year-over-year nominal GDP growth (Q2 2019). Source: BEA, Federal Reserve Board, Macrobond, RBC GAM

- Although it is hard to fathom given elevated government debt loads, there is arguably a shortage of safe debt in the world. The amount of wealth in the world is high, and some fraction of that wealth seeks the safety and liquidity of government securities. As the pool of emerging market (EM) wealth expands, the situation becomes more acute as these savers are crowding into the same developed-world debt markets as everyone else since there are few AAA- or AA-rated investment opportunities in their own markets.

- Perversely, while high debt levels should theoretically push borrowing costs higher as a risk premium is embedded, in practice it simply means that central banks must artificially restrain short-term rates to keep borrowing costs affordable for heavily-indebted economies. This is interest rate repression.

- We maintain a bond fair-value model that was originally developed by the Bank of England. While it doesn’t quite conclude that bond yields should be as low as they are today, it does argue that a normal yield is much lower than was once the case, in the range of 3% for the U.S. 10-year yield. Central banks broadly agree, having downgraded their own definitions of a “neutral” short-term rate to below 3%.

- From a substitution perspective, the longer that yields remain outright negative in Japan and Europe, the greater a downward pressure there will be on the yields of other bond markets.

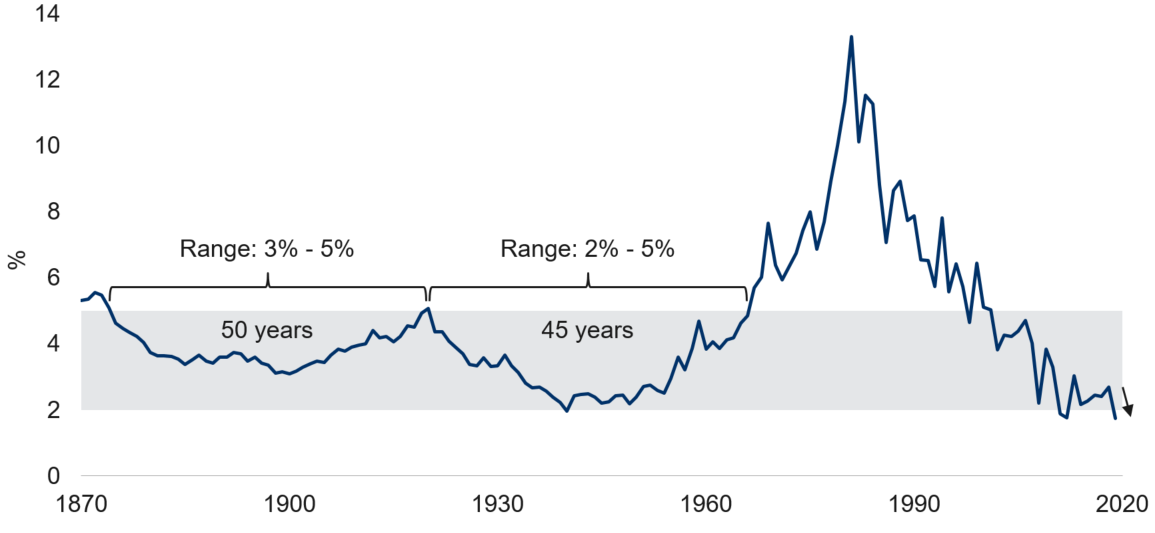

- History shows that the 1970s and 1980s were an extreme outlier to the topside for rates, and furthermore that there are multi-decade periods of time over which very low interest rates can persist (see next chart). The current episode is particularly extreme in its depth, but not in its length. The bond market is by no means overdue to rebound to significantly higher levels.

-

Historical U.S. 10-year treasury yields

Note: As of 10/16/2019. Source: RBC CM, RBC GAM

- Lastly, after this long list of structural depressants, it should be acknowledged that there are also some downward cyclical pressures on bond yields given the lateness of the business cycle and easing central banks. This isn’t a permanent condition, but it is helping to keep yields toward the lower end of their new normal range.

- Who would buy a negative-yielding bond?

- The answer is that a surprising variety of investors are willing to tolerate a negative nominal interest rate. And perhaps this shouldn’t be such a surprise since many have long put up with negative inflation-adjusted interest rates, and for even longer with negative inflation-adjusted after-tax interest rates. Those are the thresholds that truly matter for people making investment decisions – in comparison, a negative nominal yield is a fairly arbitrary development.

- Some tactical investors expect bond yields to fall further, and so to profit from the appreciation of the bond’s price to an extent that outweighs the steady drag of a negative coupon.

- Some investors are able to convert a negatively-yielding bond in a foreign market into a positive return in domestic terms by hedging out the currency risk under certain conditions. One’s home market must have the higher short-term interest rate of the two, and the foreign market must have the steeper yield curve of the two. These conditions are presently fulfilled for North American investors buying negatively-yielding European bonds, meaning that a positive return on these products is still achievable.

- Not all investors are sensitive to the expected return of a bond. The European Central Bank has purchased many European sovereign bonds with the intent of helping to depress interest rates as opposed to profit from them, and is unlikely to sell given the economic environment. Commercial banks are generally obliged to keep much of their capital in safe and liquid investments like government bonds; if the return on these bonds is negative, it is unfortunate but can’t be helped. Foreign reserve managers are similarly obliged to hold safe, liquid and usually short-term debt of foreign nations with an eye toward managing their exchange rate, not achieving a positive return.

- Other investors are sensitive to their expected return, but cannot adjust quickly or at all. As an example, an institutional investor might be mandated to hold only AAA European securities in their portfolio. They cannot buy something else unless their mandate changes – an involved process. Similarly, a pension fund may be unwilling to tolerate the risk necessary to buy higher-yielding bonds, and so they are stuck with a negative return.

- Why wouldn’t investors grappling with the prospect of a negative return simply keep their money in cash, or put it in a chequing account? Because those are not risk-free propositions, unlike a sovereign bond. Cash can be lost, destroyed or stolen. A chequing account is generally quite safe and provides deposit insurance, but this may not be sufficient for a European corporation with far more money than deposit insurance can cover and given the degree of flux in the European banking sector over the past eleven years.

- How long can low and negative interest rates last?

- This is not to say that negative interest rates will necessarily become a permanent feature of the fixed income market.

- One hopes that central banks will be able to eventually drive policy rates a little higher in the likes of Europe and Japan, though that seems like wishful thinking for the remainder of this business cycle.

- Similarly, we are hopeful that other countries will eventually follow the recent U.S. lead and manage to sustain moderately faster rates of productivity growth that will help to elevate GDP growth and thus the level of bond yields.

- Lastly, we believe Europe is less vulnerable over the long run to getting stuck in a low growth, low inflation, low rates and high debt environment than is Japan. Furthermore, the U.S. and Canada are even less vulnerable. Not all are equal in this regard.

- But the basic fact is that the great majority of the aforementioned justifications for low yields are likely to persist to varying degrees on an indefinite basis. Inflation has seemingly been tamed, barring a radical increase in the amount of public debt, the shortage of safe assets will likely persist, and so on.

- Thus, whether interest rates remain negative or not, they will probably remain quite low for the foreseeable future.

- Distortions that arise from low and negative rates:

- Low interest rates push savers into taking larger investment risks in an effort to secure some sort of return, or at least to avoid locking in guaranteed (albeit small) losses. Larger investment risks bring not just the possibility of substantial unanticipated losses, but also of diminished liquidity. This reduces the resilience of corporations and retirees alike to economic shocks.

- Negative rates encourage economic actors to rely upon cash to a greater extent, rather than suffer losses in a bank account or the bond market. This, in turn, threatens to reduce tax compliance, compromise government tax revenues and increase the incidence of theft.

- Businesses and households seek to stow their money in ways that don’t suffer from a negative interest rate. Examples include pre-paying invoices (the negative return becomes the problem of the vendor you are buying from), pre-paying one’s income tax bill as a means of getting a guaranteed 0% rate of return from the government, or even overpaying credit cards and carrying a positive balance. All of these actions distort the economic system in various ways.

- Banks are classically hurt by negative interest rates as their excess reserves no longer earn a return and as their net interest margins shrink.

- If borrowing costs are zero or even negative, then the necessary expected return on a new business project can be as little as 0%. As a result, bad ideas are put into practice.

- Borrowing naturally rises when the cost of servicing debt is extremely low. All of this extra leverage can eventually create problems, particularly were interest rates ever to rebound.

- Economic implications of low and negative rates:

- A low neutral interest rate limits the ability of monetary stimulus to rescue economies when they run into trouble. In turn, recessions could become more frequent or more severe.

- Productivity growth is damaged when low borrowing costs allow bad business investment decisions to be made.

- The aforementioned distortions and excesses create fragility within the economic system, increasing the risk of a financial crisis.

- Market implications of low and negative rates:

- Returns in the fixed income market are unavoidably low in a low or negative interest rate environment, though getting to that point can at least provide a speck of capital gains.

- In a low-rate world, a quest for yield occurs, increasing the valuations of other asset classes. This means that credit spreads should be unusually narrow and equity P/E ratios should – in theory, at least – be unusually high. This might be a profitable experience for those asset classes initially, but ultimately the steady-state rate of return of those assets should also be diminished once the situation is fully priced in.

- To the extent investors are pushed outside of their comfort zone – and into more dangerous securities – they become more vulnerable to periods of financial market volatility.