U.S. business cycle update:

- The recession models we track indicate there is no recession in the U.S. right now, but acknowledge a higher-than-normal risk in the future. For example:

- A crowd-sourced model is in the vicinity of its highest reading since 2012.

- Our financial conditions + macro model recently identified a 1-year recession risk of as high as 33% (though this has since receded to 13% as financial markets have exhaled)

- The NY Fed’s yield curve model predicts a (broadly rising) recession risk of 25% over the next year.

- Thus, the U.S. recession risk over the next year is higher than normal and non-trivial, but hardly preordained.

- Our business cycle scorecard continues to point to a “late cycle” diagnosis (see first chart, below). If this assessment is wrong, it is more likely that the cycle is even more advanced than we think, rather than that it is less advanced. However, in contrast to last quarter when the cycle assessment took a substantial leap forward, the scorecard actually took a slight step back this quarter. The “end of cycle” counterclaim weakened slightly and the “mid cycle” counterclaim strengthened.

-

U.S business cycle scorecard

U.S is "Late cycle" though slight retreat from last quarter, "End of cycle" now slightly more likely than "Mid cycle"

Legend: Dark shading indicates the most likely stage of business cycle (full weight): light shading indicates alternative interpretation (0.5 weight). Source: RBC GAM

- Behind the diminished strength of “end of cycle” claims, a number of mostly high-twitch inputs have become less worrying. This is largely because financial market conditions have improved over the past quarter. Relative to the start of 2019, volatility is now lower, credit spreads have narrowed, the equity market has resumed its upward trend and sentiment has improved. Of course, the very nature of high-twitch indicators is that they could reverse just as easily.

- On the other hand, a few of the more macro-oriented inputs are now pointing to a later point in the cycle than before. These inputs include housing, leverage, the consumer, monetary policy and bonds.

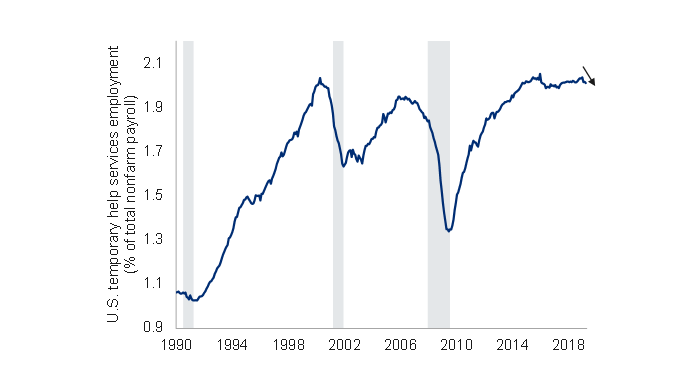

- Even among inputs which remained relatively stable, such as employment, some forward motion was visible, such as the decline in temporary jobs (see next chart).

-

U.S. temporary employment share starting to fall

Note: As of Mar 2019. Shaded represents recession. Source: BLS, Haver Analytics, RBC GAM

Modern Monetary Theory:

- Although some of the ideas behind Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) are more than a century old and the subject has attracted a degree of academic attention over the past decade, the term has only achieved significant public attention since the start of 2019 (as per Google Trends).

- This spike in interest is largely the result of a handful of prominent Democratic politicians – including presidential candidate Bernie Sanders – flirting with the idea in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election.

- A challenge in critiquing the theory is that it continues to reside more in the qualitative realm than in the form of equations, and so means something slightly different depending on the advocate.

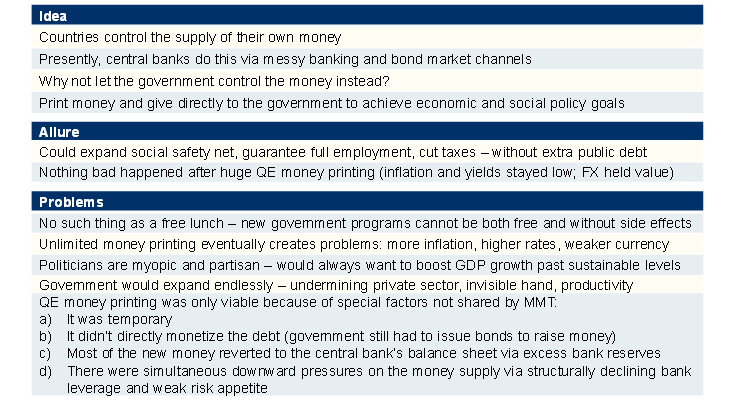

- Nevertheless, there are a few commonalities. We review the idea, its allure, and its problems. You can also find a shorter summary in the graphic that follows.

- The idea:

- Countries get to control the supply of their own currency.

- Presently, central banks manage their nation’s money supply by adjusting interest rates and engaging in open market operations.

- The central idea behind MMT is that the fiscal wing of the government should instead control the money supply.

- By doing this, governments could print money as desired and put it directly toward economic and social policy goals, rather than the present approach of allowing the money to trickle through the financial system before reaching the real economy.

- The allure:

- With a theoretically unlimited source of funds, governments could guarantee full employment, provide universal healthcare, expand the social safety net in other ways, or even cut taxes – all without increasing the national debt.

- At a time of widespread discontent with status quo policy and “elites”, alternative ideas such as MMT are enjoying particular attention.

- If the idea of printing money without immediately encountering problems sounds fanciful, recall that the large-scale quantitative easing operations of central banks over the past decade were a form of money printing, yet nothing especially bad came to pass: inflation and bond yields remained low and currencies held their value.

- Problems:

- Unfortunately, there are several problems with this idea.

- The simplest and arguably most powerful rebuttal is that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Logically, how could a massive new government program be undertaken without any cost or side-effects? Surely some brilliant king or mandarin would have stumbled upon this miracle solution over the past few millennia, if it truly worked.

- In fact, many have tried. There are countless examples of countries leaning heavily on the printing press to finance government spending. This has universally ended badly, spanning the debasement of coinage in Roman times, the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic (contributing to World War II), to more recent examples in places such as Zimbabwe, Argentina and Venezuela.

- Unlimited money printing eventually creates serious problems in the form of more inflation, higher borrowing costs and a weaker currency. How could there not be eventual inflation when more money is chasing after an unchanged amount of goods and services produced within the economy?

- To be fair, supporters of MMT argue that the goal wouldn’t be endless money printing, but merely proceeding until full employment is achieved. Furthermore, any evidence of overheating would be addressed by raising taxes or issuing debt, cooling the economy and taming inflation.

- However, it is far from clear that politicians could demonstrate such self-restraint.

- The very reason that money creation is currently outsourced to central banks is that their independence and clear mandate keeps such decision-making out of the hands of myopic, partisan politicians. Politicians are incented to maximize economic growth in the short term so as to remain in power. While this economic goal sounds inoffensive at first blush, it leads to overheating and problematic inflation if pursued relentlessly.

- Realistically, despite claims to the contrary, unlimited funding would encourage governments to expand without cease. There are always ways that a larger government could – at least superficially – improve a country’s standard of living. But, at a deeper level, such government largesse would start to interfere with crucial underpinnings of the private sector such as market forces, creative destruction and the motivation to work. Prosperity is built upon this, not unlimited money.

- Furthermore, the idea that the government would print money until full employment is achieved is not so different than the current approach. Today’s central banks already effectively pursue that aim, either explicitly (as in the case of the U.S. dual mandate) or indirectly (via inflation targeting, but with an eye on eliminating economic slack).

- But wait – central banks may be printing new money with similar motivations, but they aren’t gifting it directly to needy people, as the government could. Isn’t that a missed opportunity? Perhaps in a limited sense, as the U.S. can sustainably print around $25B to $160B of new money per year. But this only amounts to 0.5% to 4% of annual federal spending, meaning the other 96—99.5% would still need to be funded by traditional means. Furthermore, whereas a central bank can always destroy money if it realizes it printed too much, it is harder to claw back funds from said needy people. There are also distributional issues. When central banks print money, it devalues everyone’s assets roughly equally. But if the government instead showers money on a select group, the remainder bear the inflationary burden disproportionately.

- Finally, the success of quantitative easing (QE) over the past decade was very much a special case, for four reasons:

- QE was explicitly temporary, and so did not significantly undermine the credibility of central banks or host nations. The U.S. has already pulled back some of the money that was originally printed.

- Central banks did not directly monetize the debt. This is to say, they didn’t give money as a gift to the government. Instead, they purchased government bonds. This is an important difference, as the government still had to pay interest on the debt, and must eventually repay it.

- Most of the new money never actually made its way out into the real economy. Instead, banks found that there simply wasn’t an appetite for significantly more borrowing, and so they returned the bulk of the money back to the central bank in the form of excess reserves. Thus, the effective money printing was much more limited than the headline numbers suggest.

- There were special deflationary factors at work that helped to offset the normal inflationary effect. One of these is that banks were simultaneously deleveraging, reducing the money multiplier. Another is that – in particular over the first half of the QE experiment – risk aversion was considerable, providing a natural dampener on the velocity of money.

- MMT proponents could not count on such favourable conditions in their own undertakings.

- The bottom line is that MMT probably wouldn’t work as intended in a real world setting, especially if meant to be used as a permanent policy tool. A country’s currency would likely fall, its inflation rate would rise and its economy would be damaged.

- From a practical perspective, an MMT supporter is unlikely to be elected president in the 2020 election, and even if they were, the many checks and balances of the U.S. political system would make the implementation of MMT quite unlikely.

-

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

Source: RBC GAM

Fed review:

- The latest Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decision was ultimately sleepy, as expected. The U.S. Federal Reserve left its fed funds rate unchanged in the 2.25% to 2.5% range.

- The accompanying statement described economic growth as solid.

- The statement was initially interpreted in a dovish fashion by the bond market, with core inflation described as having declined and now operating below the central bank’s 2% target.

- However, that initial dovish interpretation later unwound when Fed Chair Powell described the inflation undershoot as “transitory” in the meeting’s accompanying press conference. The temporary depressants included apparel prices, drug prices and the cost of financial services.

- In the end, the Fed has made clear – as we had expected – that it is fairly far from either rate cuts or rate hikes.

- A point of clarification: the idea that weak inflation is only transitory is easy to misunderstand. It doesn’t mean that apparel, drug and financial services prices are expected to overshoot in the future to make up for their recent underperformance. It simply means they are expected to return to a more normal rate of ascent. Because central banks are tasked with targeting 2% inflation at all times, they don’t need to compensate for prior deviations.

- A final musing: we wonder whether lower drug and financial services inflation could prove more than transient, in contrast to Fed expectations. Drug prices are lower in significant part because public sentiment has turned against drug makers, politicians have held multiple hearings on the subject, and regulators are attempting to speed up the approval of generic drugs. These could prove sticky depressants. Similarly, it feels as though the financial sector is encountering greater sustained competition in the payments and wealth management spaces.

Data review:

- Nearing the conclusion of a very U.S-heavy #MacroMemo, we review some of the recent data points in the U.S.

- The ISM Manufacturing index was unexpectedly weak, falling from a solid 55.3 to a mediocre 52.8. This represents the continuation of a downward trend since late last summer, when the ISM Manufacturing peaked at a big 60.8. The latest reading is the lowest since October 2016.

- The most important subcomponents fell more than the rest, with the employment input down by 5 points and new orders down by 6.

- While a sub-50 reading is technically associated with decline in the sector, note that economy-wide recessions require a reading of around 43 or lower. The metric is still a considerable distance from that.

- Meanwhile, several other U.S. economic indicators appear to be completely fine.

- The ISM Non-Manufacturing Index fell only slightly, from 56.1 to 55.5.

- U.S. April payrolls managed the addition of 263K net new jobs. This is ahead of the recent average and even further beyond the level necessary to keep pace with population growth. The unemployment rate also achieved a new cycle low, falling from 3.8% to 3.6%.

- Despite the ISM Manufacturing print, we are still inclined to say there are more green shoots than not in the U.S. economy right now.